About The Book

Innovation to transform business, society, and people’s lives not only seems to be speeding up, it is getting quicker. As ideas build off each other and more capital is invested in these ideas, so the rate of change increases.

A look at the corporations in the Fortune 100 list of top companies by market capitalization found nearly half (forty-seven) had left the list by 2020’s ranking compared to 2000’s. Most of those dropping out of the ranking had failed to set up or run a corporate venturing unit as part of their innovation strategies.

This book defines the secrets to innovation and explains how to:

● decide how to set your aims and strategies

● develop an ecosystem for innovation

● transform with AI

● use transformational start-ups

● build a team to achieve the goals

● harness tactical factors

In the modern world, everyone needs to take control of their innovative potential to transform. This authoritative book shows them how.

There are ways to use professional approaches to capital investing to harness and transform how corporations buy, invest, and partner with third parties as well as build and accelerate internal innovation efforts.

What’s inside

Deciding the Race

Ecosystem for Innovation

Chapter 2

The AI Transformation

Transformational Start-ups

Chapter 4

Building a Team

Chapter 5

Tactical Factors

Chapter 6

Sustainability

Chapter 7

Introduction

In 1964, Roger Bannister became famous as the first person to run a mile in under four minutes—breaking a barrier that had stood for decades and many thought impossible to overcome.

Once he showed it could be done, the same barrier was broken by John Landy, an Australian runner, only forty-six days later. (Bannister and his pacers decided May 6, 1964, would be his attempt because they knew if they waited any longer that Landy—who was headed to Europe to break the barrier—would likely beat him to it.)

And, as Bill Taylor relates in a Harvard Business Review article, just a year later, three runners broke the barrier in the same race.

Once Bannister showed the possibility, that level of performance, which had never been done, became achievable. By 2019, more than 1,500 runners had completed a four-minute mile.

The same is true in innovation. Ideas are not finite goods to be hoarded and used up but spread, replicated, and built on. Disruption comes from good ideas, incrementally built on in a context and environment that support it.

The first industrial revolution shows how great leaps forward and value exponentially increased from others. The industrial revolution’s first general-purpose technology (GPT) was steam.

Perhaps the second was electricity. Ignoring advances in medicine such as painkillers and antibiotics, the third and perhaps fourth were probably semiconductors and software and the internet as part of the information and communications technology revolution.

But while these inventions had far-reaching implications, it took decades from theory, pilots, and/or patents to achieve success commercially and affect the economy significantly.

But, just as Sir Isaac Newton said he stood on the shoulders of giants before him to see further, now the interrelation of ideas and technology is speeding up change. This means we have the potential to live longer, better lives (tackling pathogens and augmenting human capabilities), use energy more sustainably (net zero while increasing production), and enjoy greater communication tools (from WhatsApp and WeChat to the metaverse).

We now move in a world of quantum and 5G, nanotech and additive manufacturing, synthetic biology and gene editing, renewable power and distributed storage, artificial intelligence, the blockchain and the metaverse. Innovation is often found at the crossover between different fields of research and the application of theoretical science into applications. It still takes time, and the role of the CEO and C-suite at corporations, as well as societies and individuals, is to juggle enough results in the shorter term while building capabilities for the longer term.

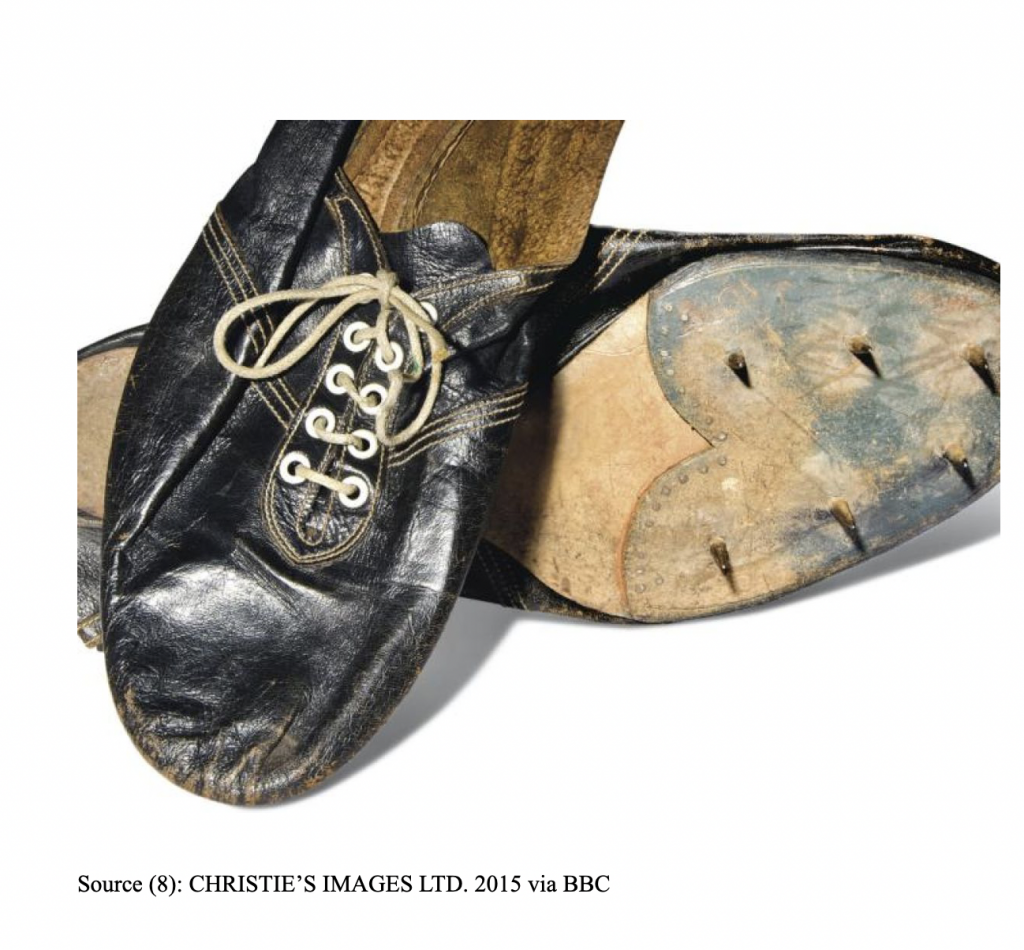

Here is the cutting-edge technology in Roger Bannister’s day: leather shoes, metal spikes, and string laces through plastic eyelets.

Then think of the time from patent to commercialization of, say, zippers or Velcro or the new materials and designs in modern running shoes, such as Nike’s new Vaporfly shoes, which utilize carbon nanofiber technology to absorb and repurpose energy. It is easily beyond a decade—twelve and thirteen years, respectively, according to Vladimir Bulović, professor of electrical engineering and computer science at MIT. The challenge is moving from idea or prototype to scale and the cost efficiencies that it can bring.

It is relatively easy for students in a laboratory to whack electrical current through a pickle and see if it glows. But it is far harder to turn this light-bulb moment into organic light-emitting diodes (OLED) where the voltage can change the color.

Venture capitalists (VCs) can turn to software rather than hardware for faster proof points of whether the idea can scale, which is why less than half of VC cash goes to hardware despite the recent revival. Corporations in physical tech or requiring digitalization and innovation, however, still need the new ideas to flow.

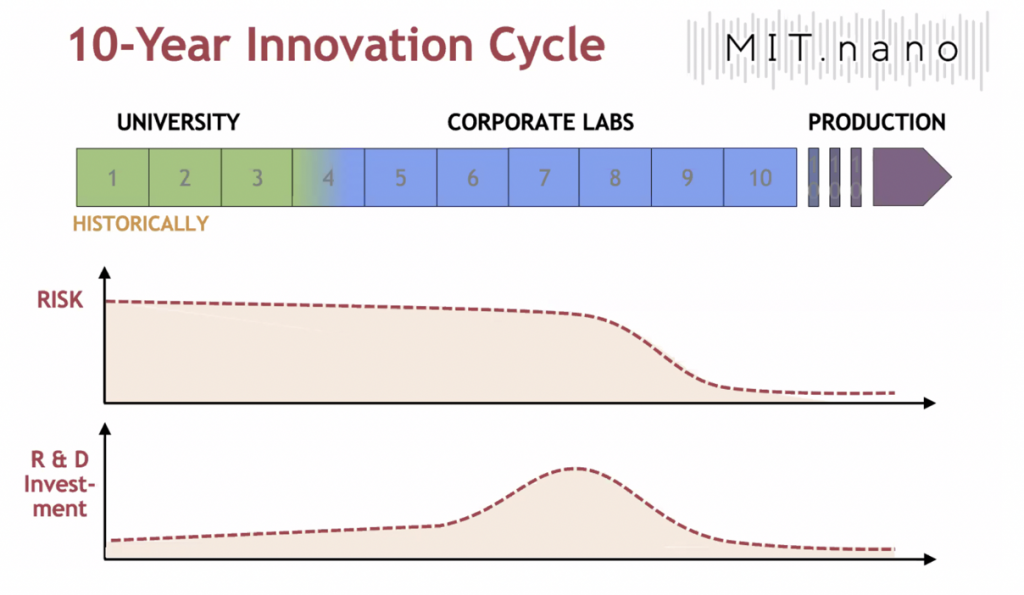

Bulović said the traditional ten-year innovation cycle usually starts with ideas forming over a few years at university before becoming a paper then presented at a conference. At the presentation, corporations could listen in for potential ideas and take them back to the corporate research and development labs for a half dozen more years’ work and then, hopefully, productionization.

Source: chart presented by Vladimir Bulović in the webinar “The Future of Advanced Manufacturing” hosted by Mach49 on November 4, 2020.

This is long, risky, and capital intensive, all of which are unappealing—especially if the average tenure of a hardware company CEO is six years, Bulović added.

CEO and management turnover was at record levels even before 2020, according to accountants PwC. CEO turnover was 17 percent in 2018 among the top 2,500 corporations, which are now often grappling with a decade’s worth of digitalization happening in the past eighteen months to many industries.

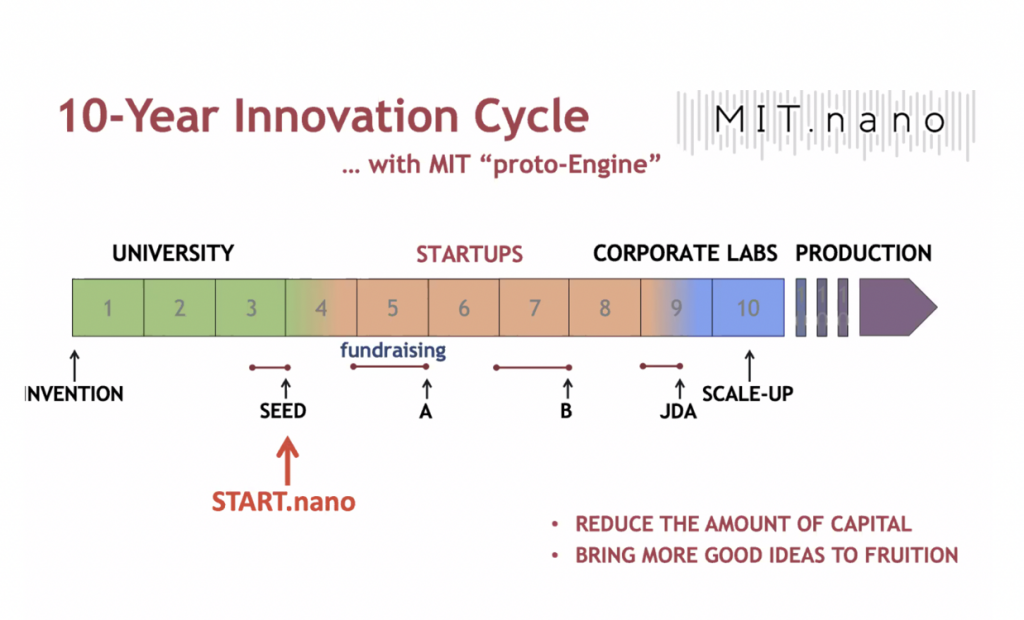

Instead, universities and corporations are turning to start-ups for the middle years of development. Here, some seed or early-stage capital allied to lab space at places like Bulović’s MIT.nano facility can reduce costs and prototype ideas, such as quantum dot OLEDs or carbon nanotube chips. In this light, it is no surprise MIT committed $25m and $35m, respectively, to VC firm the Engine’s first two deep-tech-focused funds.

Source: chart presented by Vladimir Bulović in the webinar “The Future of Advanced Manufacturing” hosted by Mach49 on November 4, 2020.

Source: chart presented by Vladimir Bulović in the webinar “The Future of Advanced Manufacturing” hosted by Mach49 on November 4, 2020.

The ideas of open innovation shared a generation ago by Clayton Christensen and Henry Chesbrough have been intellectual underpinnings for corporate venturing to take off. More than fifteen years after Clay Christensen’s disruptive innovation course and Harvard Business Review’s article on the topic, it is clear open innovation has won.

Probably all corporations now recognize that not all the smartest people work inside their walls. Innovation can happen anywhere, anytime, by anyone. But headwinds seem to be increasing in how we tackle and organize our resources to meet the next set of aims that trade wars, pandemics, stakeholder demands for shareholder returns, and climate change threaten. This creates challenges but also the opportunities for the next form of responsible innovation and a new lap for the current generation to race.

Applying these innovations to deal with the threats and opportunities around us today are the best way to sustain our world.

Christine Gulbranson and James Mawson have been on the front lines of these changes with investors, top-level start-ups, and research for more than two decades. The age of transformative innovation requires openness, teamwork, and recognition of risk and value creation.

Christine is the CEO and Managing Partner of Nova Global Ventures, a tech-agnostic fund specializing in AI and disruptive technology partnering with Global Corporate Venturing. She was the CEO and director of a private family foundation office for impact investing, chief innovation officer of the University of California System, a general partner at VC firm GCP, and senior investment adviser to a family office in Europe. She was a judge on Discovery Channel’s Big Brain Theory to find the “next great American innovator,” which aired in over one hundred countries, as well as a scientist at LLNL. Christine has served for over twenty years as a director on more than a dozen private and public service boards and has been recognized by Silicon Valley Business Journal as one of the top forty under forty business leaders in Silicon Valley, as innovator for the twenty-first century by Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) Technology Review, and as University of California (UC) Davis’s distinguished engineering alumni in business.

Christine grew up in rural Northern California and Germany and is a first-generation college graduate. By age twenty-five, she earned five degrees from UC Davis—BS in physics, a BS, MS, and PhD in materials science and engineering, and an MBA. She holds patents in the fields of nanotechnology and lighting.

Website: http://christinegulbranson.com/

This GCV title was followed by the launch of the second publication, Global University Venturing, in January 2012 to help students and faculty and academia more broadly launch or develop their entrepreneurial businesses and work with external peers. Mawsonia’s third title, Global Government Venturing, was launched in May 2014 and rebranded to Global Impact Venturing in February 2019.

As well as previously editing Private Equity News, James coordinated leveraged buyout and venture capital coverage for use by other titles in the Dow Jones and News Corporation group, acted as a spokesman on BBC radio and television, and chaired awards and conferences for a host of media groups, including the BVCA awards and event for more than one thousand people in October 2009.

Previously, James had freelanced for a host of national and trade media titles, including the BBC, Financial Times, the Economist, Independent on Sunday, Sunday Express, and Dow Jones Newswires; provided research for Nick Davies’s book, Flat Earth News; was a foreign correspondent in central and eastern Europe; and was international editor for FT Business.

After graduating from King’s College, London, James’s first job was working at technology publishing house ComputerWire. He is chairman of his local cricket club and ex-chairman of Radar.AI and a former director of the London Press Club.

Website: www.globalventuring.com